The local police department is addressing a drug problem with only 10 officers to patrol the 75- mile radius of the Star City. This is a story about a few people trying to end the crisis and some of the roadblocks they face.

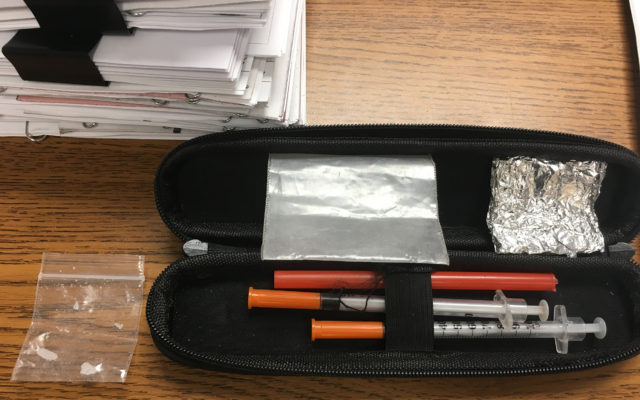

PRESQUE ISLE, Maine — Dozens of deceptively friendly, smiling faces with black eyes printed on a yellow backdrop hid the contents of a small plastic bag. It was found stashed on a shelf in the toy section of a Madawaska store. Inside, was a substance law enforcement is beginning to find more often in Aroostook County — methamphetamine.

Just over an hour south, Presque Isle police officers warned their citizens to be wary of hypodermic needles discarded around the city as more and more residents complained about finding them on the streets, in parks and even at the playground.

Far and away, the drug problem is invading some of the most vulnerable parts of The County. And according to Mark Barnes, a sergeant at Presque Isle Police Department, it’s only getting worse.

The Presque Isle Police Department covers about a 75 square-mile territory. Since January, its officers have made 619 arrests in the city. While this number includes all kinds of arrests, 60 of them were for drug-related crimes. So far this year, the department has logged 20 more arrests for drug offenses than they had during the previous year — and they’re doing it with fewer patrol officers than usual.

- Sgt. Mark Barnes displays a list on his computer of more than 30 openings for law enforcement positions in Maine, some have been vacant since April. Photo taken on Aug. 8, 2019. (Nina Mahaleris/The Star-Herald).

Across city lines, Caribou Police Department, which covers 79 square miles, has charged 16 people with drug-related crimes in the last eight months, according to an administrator.

The Presque Isle department finds itself in a position of being more reactive than proactive in responding to the growing drug problem because of the shortage of patrol officers. Chief Laurie Kelly said they have to “triage” calls, meaning they respond to the most urgent ones first and delay others — but they all get answered.

While the department is doing the best it can with a condensed staff, the shortage may represent a bigger issue plaguing police departments around the state and beyond.

Maine agencies have struggled the last few years to keep their departments fully staffed, especially in small towns. But shortages are not exclusive to small-town or rural areas; larger municipalities, too, are experiencing personnel loss. Bangor Police Department, for example, has lost one third of its officers since 2013, according to Bangor Daily News.

Six years later, Bangor Police Department still appears to be having trouble maintaining its staffing levels. The department currently is trying to fill six open patrol positions, according to Deputy David Bushey.

- A case containing needles and a substance believed to be methamphetamine lays out on the desk of Sgt. Mark Barnes. While working the night shift on July 24, another officer seized the case after a pedestrian found it on Main Street in Presque Isle. (Nina Mahaleris/The Star-Herald).

The time and cost to become a trained law enforcement officer could be a contributing factor to the general shortage of officers. According to Presque Isle’s Chief Kelly, it can take up to a year, sometimes more, to fully train an officer — and it can be costly.

In Presque Isle, general training costs for each new officer can amount to more than $52,000. And even with that investment, a total of 32 officers have left the department in the last decade.

Seven retired in that time while another 25 resigned, according to Kellie Chapman, human resources director for the city.

Chief Kelly said this turnover is indicative of the statewide competitive climate in the profession.

“Law enforcement’s really competitive … everybody’s short-staffed,” she said. A general decline of people entering law enforcement and the rigorous standards candidates must meet could contribute to the competitive nature of the field.

The falling numbers of people entering law enforcement isn’t just a Maine problem. It’s prevalent nationwide. A study from the Bureau of Justice Statistics revealed that the number of full-time sworn-in, local police officers in the United States decreased by about 9,000 between 2013 and 2016.

Kelly said the Presque Isle department is facing a larger issue of losing officers to agencies in Southern Maine and beyond. Presque Isle’s officers are leaving for a variety of reasons, she said, but the biggest one is related to the department’s inability to compete with agencies that offer defined benefits packages.

“That’s what they’re leaving for,” she said.

Presque Isle City Council has opened discussions about a possible return to the Maine Public Employees Retirement System, which offers the defined benefits plan similar to Social Security that Kelly said her officers are seeking.

In a memorandum to the council, City Manager Martin Puckett outlined the advantages to switching back to the Maine State Retirement plan, citing that returning to the Maine Public Employees Retirement System could substantially reduce training costs to the city and improve employee retention.

Presque Isle once offered this plan to city employees but withdrew it in June 1996, according to Deanna Doyle, the participating local district plan administrator for the state retirement plan.

Presque Isle police officers started contacting the agency about rejoining the plan more than six months ago. In March, town officials began “seriously inquiring” about re-establishing the state retirement plan, Doyle said.

Acknowledging the loss of officers citywide, Puckett wrote in a letter to the council, “While we may be unable to compete with federal jobs, other local departments have similar wages, but they offer [state retirement], which puts us in a considerable disadvantage.”

Since 2006, the city has paid $581,304 in training costs for new police officers, Puckett stated. In addition, he wrote that the majority of the current officers have less than five years of experience and only three have more than 10 years.

The letter also noted that the department has conditionally hired four new officers, which still leaves two fully vacant positions.

Experiencing similar challenges of retaining their staff, police departments around the state are looking for creative ways to entice officers to work. In Westbrook, the department is offering a $14,000 signing bonus for fully trained officers with at least five years of experience.

In Fort Kent, the police department is advertising for two full-time officers and began offering the state retirement plan as of July 1, with a $2,500 sign-on bonus as enticements.

Caribou Police Chief Michael Gahagan said that his department has felt similar impacts from the staffing issue. The department once went eight months without receiving a single job application, he said.

Public perception of police officers could be a reason for the loss of qualified applicants in Maine, but what some people may forget, Presque Isle’s Sgt. Barnes said, is that law enforcement isn’t what people might think or see on television.

There are indeed split-second decisions that must be made — decisions that can have fatal consequences for themselves or others. But the job also involves a lot of paperwork — much more than people may assume. Barnes said it can take up to three hours to write incident reports and search warrants, which are important tasks associated with the job.

Also, if officers don’t follow important steps, they risk having cases dismissed, Barnes said.

Officers, for instance, can’t break into a house where neighbors might think drug activity is happening, he said, because criminals also are protected by their constitutional rights. Officers must take the necessary legal steps, like obtaining a search warrant or seizing evidence of illegal substances — before arresting someone for breaking the law.

To add to the staffing issue, entering the profession is more difficult than it appears. “There’s such strict criteria to get into the field,” said Kelly. Applicants have to pass numerous tests, including a polygraph, a psychological exam and a physical fitness test.

In addition, they need to graduate from the Maine Criminal Justice Academy, an 18-week residential training program on being a police officer, before they can work as a fully trained officer.

The Academy offers a few sessions per year and takes only 66 students each session. Law enforcement agencies cover the $2,500 tuition cost for officers they send to the MCJA. That doesn’t include other expenses such as uniforms and psych and polygraph tests, which can cost more than $900.

In Presque Isle, these expenses come out of the city budget.

The 66-student limit per session is to ensure the success of their “hands-on” program and maintain the student-teacher ratio, said MCJA Training Director Rick Desjardins. The academy isn’t just teaching civilians how to be law enforcement officers, though. Students also learn how to manage the stress and demands that can accompany the job, he said.

When Desjardins first started his career in law enforcement in the 1980s, he said it was “almost unheard of to have conversations about feelings.” Now, MCJA trains officers to deal with the everyday physical, emotional and mental stresses of their jobs.

“If you don’t help people at least practice what stress does to them, stress can be paralyzing,” he said.

Desjardins said that mental health needs to become part of the culture in Maine, especially within law enforcement, so that people can learn to ask for help when it’s needed. Officers need to learn to accept their own issues and be honest about their emotions.

Even more, officers need to become comfortable with things that might prove difficult for the average person to reconcile. Death, domestic violence, car accidents and drug overdoses can be parts of the things they see everyday.

“There’s gonna be difficult scenes that they’re going to [have to] deal with,” said Desjardins.

Agencies also have to recognize officers may have trouble witnessing disturbing scenes, said Desjardins, and should train officers to deal with the aftermath of such sights.

Desjardins said that stress and challenges to mental health can become “part of the game,” and that officers need to be accountable for themselves when they need help. He emphasized that every case is different and officers each have their own methods for dealing with stress.

For Barnes, it’s just part of the duty he took on 29 years ago. He sees people on their “worst days,” and he’s accepted that witnessing tragedy can just be another part of the job. Barnes said that earlier this year, he was the first Presque Isle officer to respond to a crisis call that resulted in the deaths of a 14-month-old baby and his father. Although he didn’t go inside the home, Barnes noted that responding to these kinds of events can be particularly difficult. While it’s all a part of his job, “it’s not getting any easier” to deal with.

“I can’t count how many dead bodies I’ve seen,” he said.

Barnes pointed out that police aren’t the only ones who can help bring an end to the drug crisis. Community members can work with the department in ways such as taking down license plate numbers of those suspected to be breaking the law, said Barnes.

Caribou Police Chief Gahagan said that while the drug problem may not be overtaking The County yet, the prevalence of drugs in the area could be representative of more to come.

“It’s not bad here … but it’s coming,” he said.

Next: Maine organizations and treatment centers dedicate themselves to fighting the drug problem, one life at a time. Read about substance use disorder from their perspective in the next installment of “Deadly Dilemma.”

Deadly Dilemma is a series of occasional stories about the consequences of the increasing drug problem in Aroostook County. The series will feature stories on various community members, families, spouses, organizations and others who are affected. To find help near you for addiction, call 211 or visit www.211maine.org.