Recent advancements in DNA ancestry research have led a northern Maine French teacher to an unexpected discovery: more than 80% of his students have Indigenous ancestors.

Fort Kent French teacher Robert Daigle has been tracing students’ ancestry back to Europe for several years. This typically culminates in a cultural exchange between students in France and Fort Kent.

But breakthroughs in genealogical research via DNA have allowed Daigle to show his students not only where their forbears lived before traveling to the United States, but that many have Indigenous ancestors who have always lived in North America. The discovery shows that for many with Acadian heritage, their roots are more diverse than they imagined.

The students are enthused about the connections.

“When I first discovered I had Native American heritage, it made me appreciate the area I live in, but also my ancestors as well,” 11th grader Kaylen Theriault said. “I am proud to say that I am part of another culture, and am positively impacted by this discovery.”

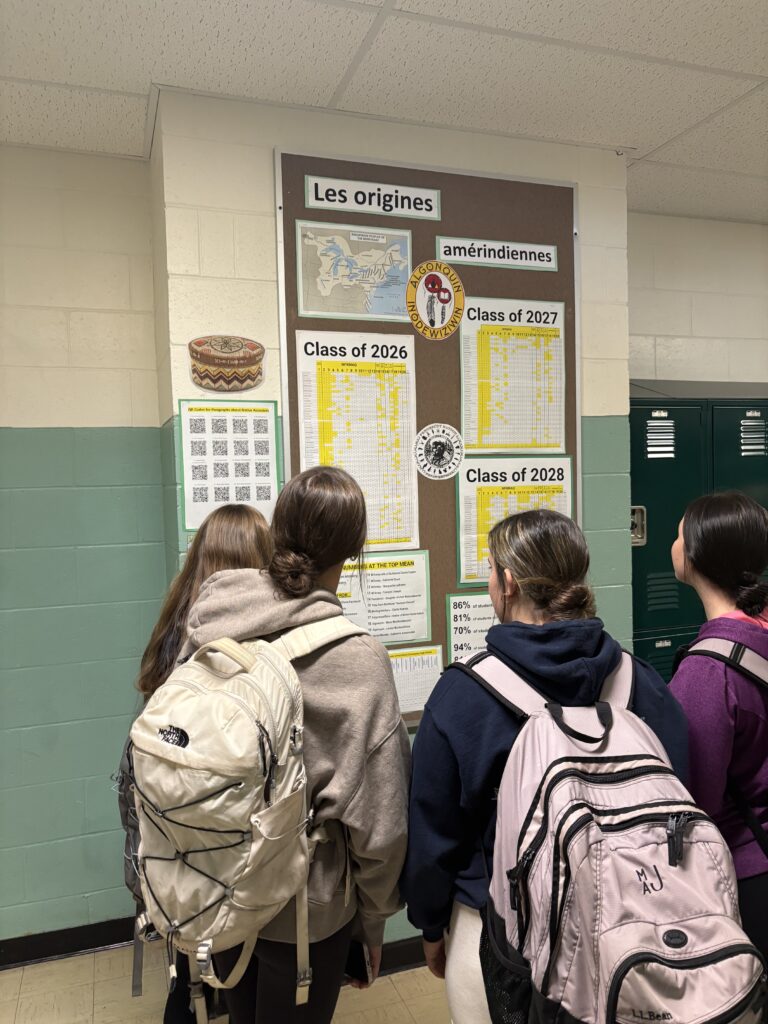

Daigle’s research showed that 87% of his 331 students had French ancestry, 81% had Indigenous ancestry and 70% specifically had Mi’kmaq ancestors. Of those with French ancestry, 93% also have Indigenous roots.

Daigle found that 18 Indigenous ancestors appeared continually in his research, including Maria Olivier (Manitouabeouich) Sylvestre, Anne Marie Mi’kmaq, and Jeanne Maie Kagigconiac. He expects to find more common Indigenous ancestors — as he did with his own family.

“Since the age of 11, and since the first Acadian festival, family history has always been something that has interested me,” he said. “As an educator, I believe that these types of statistics require an educational response.”

Daigle has been fascinated by genealogy since Madawaska launched its Acadian Festival nearly 50 years ago, he said. The event hosts reunions of local families, and the Daigle family was the first to be featured.

He learned about his ancestry from family trees, produced at that time by a professor at the University of Maine at Fort Kent, and local newspaper articles about Acadian heritage.

But it wasn’t until 2014 that Daigle discovered that he had an Indigenous ancestor. He then found a group online called the Mothers of Acadia that submit their DNA for testing. The name comes from the fact that there are approximately 60 mothers for the entire Acadian population, and that DNA testing has shown that many of these mothers are Indigenous to North America, he said.

“It was the advent of mitochondrial DNA and Y-DNA in genealogical research that kind of broke the code,” he said.

Mitochondrial DNA is inherited from the maternal side.

Much of Daigle’s research was conducted at the University of Maine at Fort Kent’s Acadian Archives, Archives Director Patrick Lacroix said, adding Daigle is methodical in his research and has a keen understanding of the available documentation and DNA evidence.

“Only a small minority of Acadians married Indigenous people,” Lacroix said. “However, the Acadian population was itself quite small in the colonial period. Families intermarried, such that over the course of generations, more and more people were able to claim Indigenous ancestry.”

Lacroix said there is an interesting contrast with the French Canadians descended from the early settlers of Quebec. Cross-cultural marriage was just as rare, but the founding population was much larger than it was with Acadians.

“For instance, I grew up in Quebec and have found no Indigenous ancestor in my lineage,” Lacroix said.

But because many Acadians and French Canadians married one another in the St. John Valley, it’s easier to find a branch in a family tree that leads to an Indigenous ancestor, he said.

Daigle’s students were fascinated to learn about their heritage. 10th grader Steven Morris said he knew he was Native American, but he was surprised to learn where that heritage came from.

“Through this project I’ve found that while I do have Native ancestry, it’s from a completely different area,” he said. “The Native ancestry I do have isn’t even from the area my whole family thinks it is.”

He expected to find those roots on his father’s side, but didn’t, he said.

10th grader Collin Harvey said he felt honored to have Indigenous heritage and is curious about his connections to his classmates.

Mercedes Horst, who is also a 10th grader, has Indigenous heritage from her mother, who is from El Salvador.

“I thought it was really cool when I found out that most of my classmates and peers have Native American ancestry,” she said. “When you think about it, they all somehow connect through this.”

Ryan Griffeth, who is in 11th grade, was surprised to learn so many students have Native ancestry. Discovering his own roots made him more curious about the history of the tribes in the area and how they have shaped communities, he said.

Each year around Indigenous Peoples Day, Daigle displays two bulletin boards at school that show statistics related to students’ heritage and their specific Indigenous ancestors.

While conducting this research takes time and effort, his students’ reactions make it all worthwhile.

“Watching the reaction of my students to the information that I was sharing is what has motivated me to keep doing the background research that I do every year,” he said.