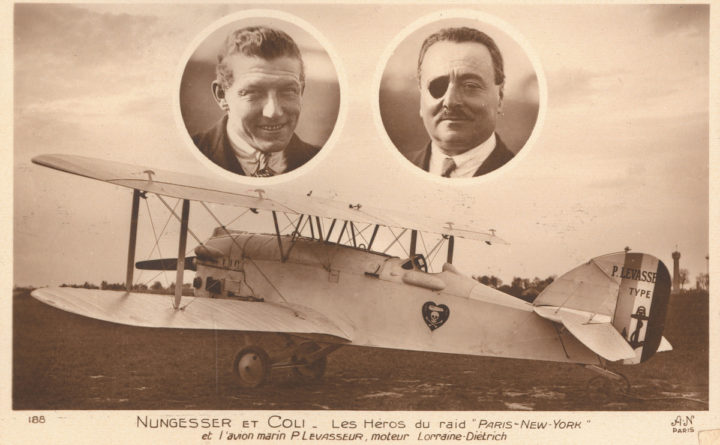

It’s fun to speculate how the course of history might have changed had one thing happened, or not happened. For instance: What if Charles Lindbergh had not been the first person to fly non-stop between New York and Paris? What if, instead, Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli, the two French aviators piloting the plane L’Oiseau Blanc, had made the transatlantic flight first?

Nungesser and Coli were trying to do just that — from Paris to New York, in their case — less than two weeks before Lindbergh successfully flew his plane, Spirit of St. Louis, along the same route. Both were vying for the Orteig Prize, which would award $25,000 (around $360,000 in 2019 dollars) to the first pilots to fly non-stop between Paris and New York, in either direction.

Unfortunately for the two French pilots, L’Oiseau Blanc — the White Bird — crashed sometime on May 9, 1927, supposedly somewhere between Newfoundland and Maine.

Twelve days later, on May 21, Lindbergh touched down in Paris, where about 150,000 cheering people met him at Le Bourget Airport. The fervor with which his feat was greeted was one of the catalysts for the development of commercial air travel as we know it, and it cemented Lindbergh’s seemingly eternal fame.

That’s not to say there haven’t been attempts to find it, however. The leading theories as to where the plane crashed are that it either went down at sea, crashed somewhere in Newfoundland, or met its fate in the woods of Maine’s Washington County.

Peter Noddin, former president of the Maine Aviation Historical Society and a self-described “amateur aviation archaeologist,” has searched for — and sometimes found — crashed planes all over Maine. Finding the “White Bird” is one of the “big ones” for him and his fellow aviation history enthusiasts.

Among the best known claims are that L’Oiseau Blanc crashed in Washington County. A local man named Anson Berry claimed he heard a plane crash near his camp on Round Lake, about 10 miles northwest of Eastport, on the afternoon of May 9, 1927. In 1980, Northeast Harbor resident Gunnar Hansen (the same Gunnar Hansen who played Leatherface in “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre”) was working on a story about the crash for Yankee Magazine, and tracked down other Washington County residents who knew the long-dead Berry, and who claimed to have also heard a plane crash. That’s about as far as Hansen got in tracking down any more leads.

“Planes over Washington County back in those days would have been extremely rare, so it is possible that Anson Berry and others did hear a plane,” said Noddin. “But the area around Round Pond has been really, really well investigated, and so far, nothing has been found.”

In 1989, the White Bird was featured on an episode of “Unsolved Mysteries.” It featured an interview with a Maine hunter, Jim Reed, who claimed in 1971 to have come across what appeared to be an airplane engine out in the woods in Washington County. The engine was too heavy for him to move alone, and when he tried to find it again later, he couldn’t locate it.

In the 1990s searches were held outside of Washington County, including on Big Spruce Mountain, not far from Gulf Hagas in Piscataquis County, and on several mountains in the Hancock County town of Sullivan. Neither search turned up any convincing evidence, and Noddin doesn’t think either of those theories is correct.

Searches continue today, and Noddin himself looked for the White Bird as recently as last year. He receives inquiries about supposed evidence of the crash regularly, and has devised a series of questions for people who think they may have found the plane to see if their theories hold any water.

He admits that the odds of anyone finding it are slim. But that’s not going to stop him and others from looking.

Noddin has long had a contingency plan should he find convincing material evidence of the White Bird crash, including calling in professional aviation recovery experts to examine and excavate the site. Noddin says that the only parts of the plane that have likely survived this long would be the engine or fuel tank, though it’s possible items from Nungesser or Coli could have survived.

In particular, Nungesser — a legendarily thrill-seeking daredevil known in France as the “Knight of Death,” and who broke nearly every bone in his body over the course of his career — had a prosthetic jaw, made of steel.

This article originally appeared on www.bangordailynews.com.