In the wake of his loss to Democrat Jared Golden earlier this month in the 2nd Congressional District race, Republican Bruce Poliquin is challenging the legality of Maine’s ranked-choice voting law and the runoff process itself.

Poliquin and his campaign are requesting a recount and have characterized the runoff as mysterious and opaque, and say that it’s run by artificial intelligence or machines that make their own decisions. But two men who decided to recreate the runoff process, the first ever used in a congressional race, say it was basically just math.

When Poliquin addressed reporters at the Portland International Jetport on Tuesday, he described the ranked-choice runoff software that determined the results as a “black box.” In science or technology a black box often refers to a device that performs a task, but whose inner workings are either hidden or not understood by the user. And that, he said, is one reason why he’s asking for a recount — a hand counting of the ballots.

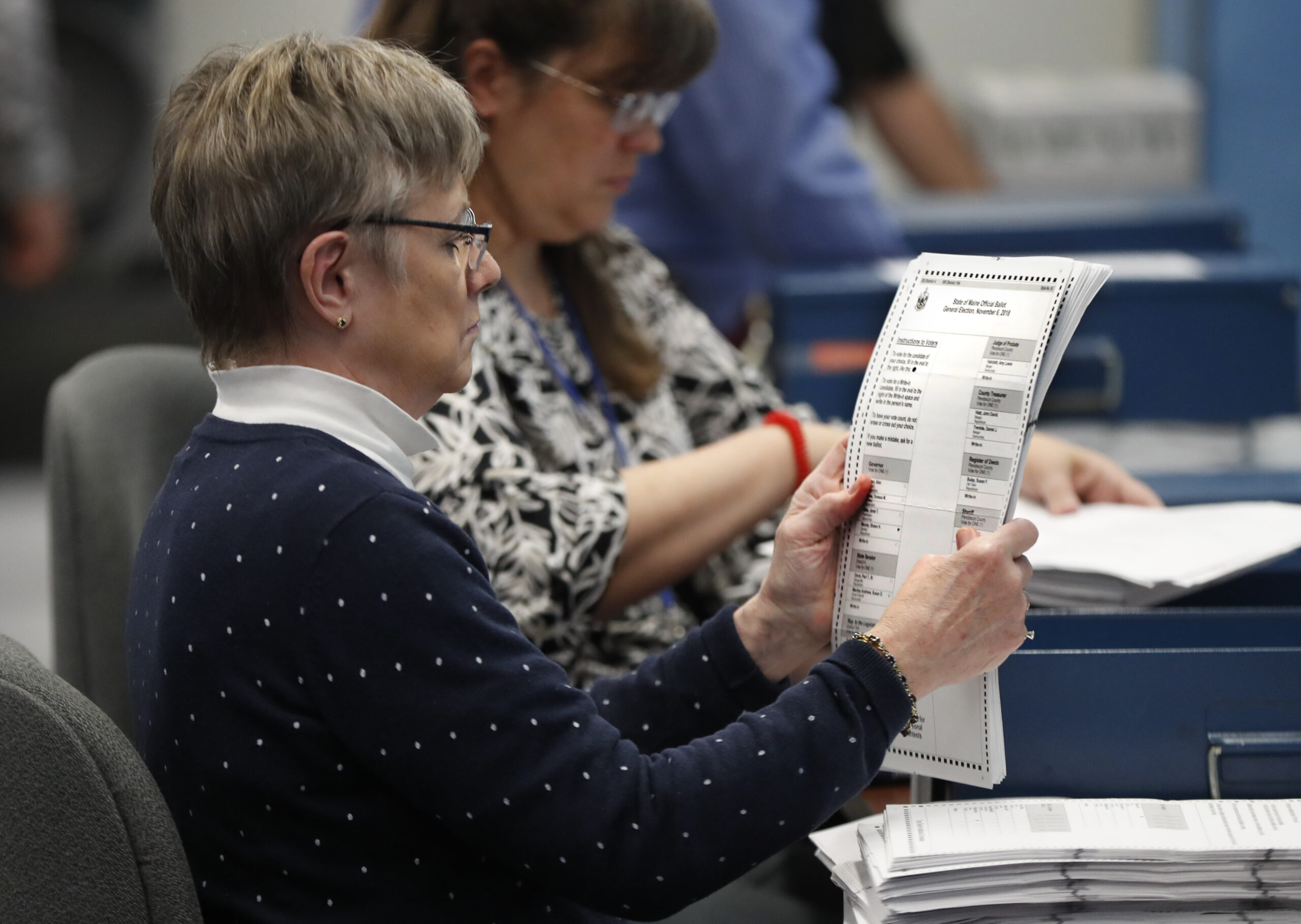

“I think it’s time that we have real ballots, counted by real people. Real ballots counted by real people, instead of this black box that computes who wins and who loses,” Poliquin said.

[Poliquin’s bid for a 2nd District revote has almost no historic precedent]

“I am a real person,” said Nathan Tefft, an associate professor and the chair of economics at Bates College in Lewiston.

Tefft said he took great interest in the news reports of Poliquin’s request recount, especially when he learned that Poliquin’s spokesperson had suggested that the counting software was powered by artificial intelligence. Tefft set out to see if he could come up with the same results that state election officials had.

“You know, I’m a data analyst in many ways, and I like to work with data,” he said. “So this was an interesting challenge for me personally just to try and be able to replicate the process.”

The Maine secretary of state’s office has published all the election results on its website — every ballot, every ranking in every town. It’s all there in massive data files that can be inspected and downloaded.

So Tefft took that data and plugged it into Python, a program that allows users to write code that calculates the data — in this case, to simulate the ranked-choice election. Now, it’s true that the software the state uses is proprietary. But the rules that are used by that software are just as public as the election results.

“Because the rules are publicly available I could implement those rules myself and then replicate the process directly,” he said.

[Maine led the nation with ranked-choice voting. Will others follow?]

So that’s what Tefft did, plugging in rules for all the various ballot scenarios. After about six hours, Tefft came up with a final tally for the election and the runoff: Golden received 50.62 percent of the vote, and Poliquin received 49.38 percent.

The state results? 50.62 percent for Golden, 49.38 for Poliquin.

“Yeah, it’s just math,” Tefft said. “There’s no sort of statistical analysis. There’s no prediction involved, which is necessarily a part of artificial intelligence, by the way.”

While Tefft does have a Ph.D. in economics, he is not the only one who has been able to use publicly available data to replicate the election count. Theo Landsman, a researcher at FairVote, a group that supports ranked-choice voting, came up with similar results using a different program: Microsoft Excel, a database program that was originally introduced in 1985.

“I was able to get the total numbers, basically, totally accurate,” Landsman said. “My first round counts and final round counts correspond exactly to what’s in the secretary of state’s database.”

Landsman’s simulation is a huge data file, but he shared it with Maine Public Radio. Tefft publicly posted his simulation, and exactly how he did it, on Github, a website that allows programmers to share their work with anyone who wants to test it for themselves.

Tefft said it wasn’t just curiosity that motivated him to replicate the ranked-choice runoff.

“It’s an important idea for me, as well, to support trust and confidence in the vote counting process. So I certainly wanted it to be as transparent as possible,” he said.

[Judge to hear Poliquin’s ranked-choice objections, request to be declared the winner on Dec. 5]

Landsman said that neither he nor Tefft could have replicated the election if the state had run an opaque vote count or not made the ballot data available to the public.

“Contrary to the black-box narrative, we have more information about how Maine ran the RCV tabulation for this race and how the votes were counted, than we have about basically any other election in the U.S. this cycle for Congress,” he said.

That, Landsman said, is something that he thinks Maine voters should keep in mind when assessing the political rhetoric about the ranked-choice process and a recount that’s expected to take about a month.

Poliquin’s campaign did not respond to request for comment at the time of publication.

This article appears through a media partnership with Maine Public.

This article originally appeared on www.bangordailynews.com.